September 2019. On 19 June, the European General Court ruled that adidas’ registration of its trademark consisting of three vertical black stripes was invalid. Despite submitting no less than 1,200 pages of evidence, the sportswear giant failed to convince the Court that its simple three-stripe trademark had acquired sufficient distinctiveness in the EU. So what lessons can we draw from this seemingly surprising decision?

European registration of the adidas three-stripe trademark no. 12442166 declared invalid

1-Register your trademark as you mean to

Unfortunately, the only conclusion we can reach is that in retrospect, adidas simply made a mistake when it registered its trademark. The relevant documents show that it actually meant to claim the three parallel stripes as a pattern; in other words, as a series of continuous stripes (in theory of any length) on clothing. However, the Court concluded that what it had actually registered was not a continuous three-stripe pattern but simply a logo: a device mark consisting of a right angle formed by three black stripes.

When it submitted its application, adidas therefore failed to mention in the description that the registration was for a pattern mark. In the event, the trademark was filed as a device mark with the accompanying description ‘The trademark consists of three evenly-spaced stripes of equal length, applied to the product facing either way.’ According to the Court, nothing in the application stated that it was adidas’ intention to claim a three-stripe pattern; consequently the application was taken to be simply for a logo.

Unsurprisingly, adidas’ 1,200 pages of evidence failed to demonstrate the use and familiarity of the trademark since the company simply never uses this right-angled logo with black stripes.

2-If you’re using white stripes, don’t register black ones!

Adidas’ sports clothing features mainly white or light-coloured stripes against a dark background. However, the trademark it registered shows black (or dark) stripes against a white (or light-coloured) background. The Court maintained that almost all the evidence adidas submitted to support its case related to the use of white stripes. So even if it had provided several box-loads of documentary evidence, none of it would have demonstrated the and acquired distinctiveness of a trademark with black stripes.

Examples of proof submitted by adidas: no use of the device mark right

3-Make sure your market research is watertight

The Court was equally unimpressed by all the market research adidas submitted as evidence of the acquired distinctiveness of its trademark throughout the EU. It dismissed 18 of the 23 (!) market surveys, arguing that they weren’t relevant to the trademark under dispute. The Court accepted that while the remaining five surveys were ‘to some degree’ relevant, they had only been carried out in five EU member states – too few to show evidence of familiarity throughout the EU as a whole. It also queried some of the questions posed in the surveys.

All in all, then, if you’re going to use (costly) market research to prove the familiarity of your trademark, make sure it’s relevant and watertight.

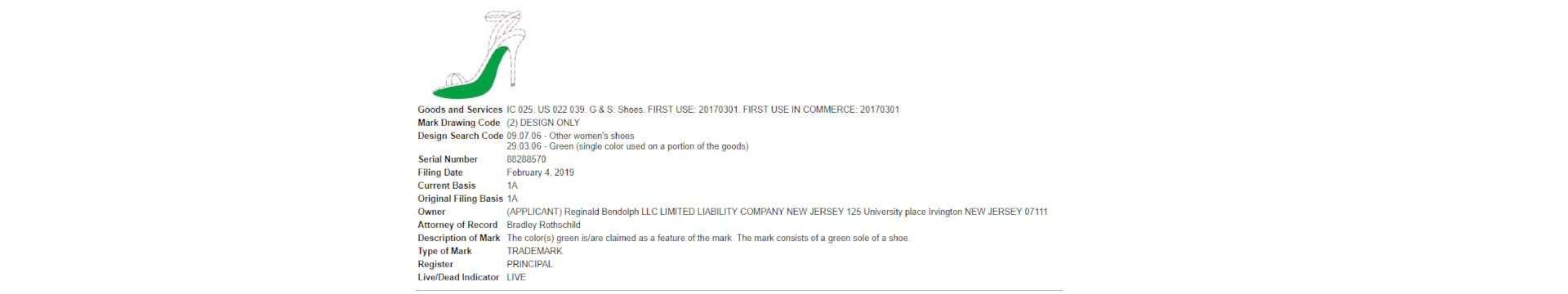

Shoe Branding

The case against the European registration of adidas’ trademark was brought by the Belgian firm Shoe Branding, which is keen to benefit from the similarity of its own trademark to that of the adidas stripes. Adidas can of course appeal to the European Court of Justice to overturn the ruling, and we’d be amazed if it didn’t do so.