Image and sound as a marketing tool

In Europe it has been possible to get trademark protection for multimedia marks, such as advertising or animation films since 2017. With this amendment, the European legislator wanted to pave the way for the registration of ‘new’ marks. Nowadays, in addition to word marks and logos, companies also extensively use image and sound as means of distinction in their online marketing communication.

Unclear criteria

However, it remained unclear until now what the criteria were to register an animated film as a trade mark. A short film is, of course, substantially different to a simple word mark or logo. How do you assess whether a film functions as a trade mark? When is this type of short film distinctive? These are questions that the courts should have answered over time.

Super Simon test case

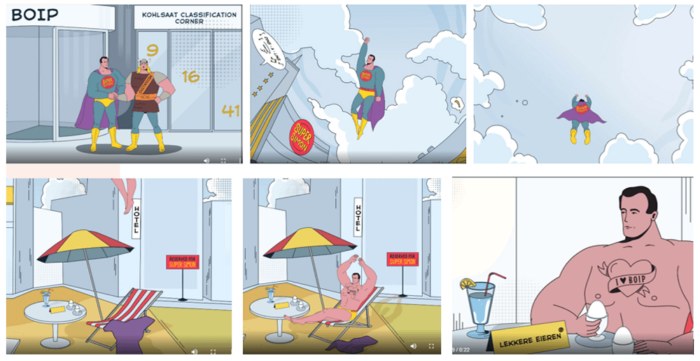

Chiever decided not to sit back and wait for that to happen. To clarify the criteria for the protection of multimedia marks, we started a test case. We applied for European registration for a film that we had made earlier for the farewell of Mr L. Simon, director of the Benelux Trademark Office. In the animation you see Simon say goodbye to his colleagues and fly off to a sunny place as a Superman lookalike, where he takes a seat poolside with a nice drink. We applied for European registration as a trademark for, among other things, books, wine and cultural activities.

Refused

Initially in 2021, EUIPO refused the registration. According to EUIPO, the film lacks distinctiveness. It’s just a nice funny film, but it is not distinctive, it does not refer to a company as an indication of origin, according to EUIPO. The film also does not refer to the goods and services identified in the trademark application (e.g. wine or books). Moreover, it doesn’t include the identity of the manufacturers or the name of a company or owner, so you don’t know who the message is from. For a film clip like this to function as a trademark, one of the requirements is that the owner is mentioned, in the same way as it is done in TV commercials, says EUIPO.

Appeal: registration after all

Chiever appealed the refusal, and did so successfully. On March the 7th, 2023, the EUIPO Board of Appeal decided that the animated film can be protected as a trademark. For the first time, the Board of Appeal has now clarified what you need to take into account when registering a trademark for multimedia marks in Europe. Below we highlight the most important elements of the ruling. You can find the full original decision here (in Dutch) together with an English translation here.

The main considerations of the EUIPO Board of Appeal in the Super Simon case:

-

- The consumer does not have to remember all the details. A multimedia brand (an animation film) is by nature a complex trademark, in which the consumer is confronted with a wide variety of images, sounds and words. However, for a film like this to be accepted as a trademark registration, the length or complexity of the animation film itself is not important. The point is that the consumer can see the film as an indication of origin, as a distinguishing mark. According to the Board of Appeal, the main character in this video Super Simon is distinctive. After watching the video, the public will mainly remember that Simon flies off to his holiday destination. This satisfies the requirement of distinctiveness. It is unnecessary and irrelevant for acceptance of the registration that the consumer remembers all details from the video.

- No heavier demands on multimedia trademarks. No stricter requirements may be imposed on multimedia marks than on ‘ordinary’ trademarks, such as wordmarks or logos. A multimedia mark therefore does not have to show the owner. After all, that’s not a requirement for a wordmark. For example: the wordmark Milka also doesn’t show that Mondelēz is the company behind the brand!

- Not a TV commercial. You cannot compare a multimedia mark with a TV commercial. Both have different purposes. A TV commercial is an advertisement that often provides information about the product. A (multimedia) trademark usually doesn’t contain (product) information, but is intended as a distinctive sign. In any case, you cannot expect a multimedia mark to include the related product and owner information, as is often the case in a TV commercial.

Conclusion

For the first time, the ruling in this test case provides businesses throughout Europe with clear guidelines when registering multimedia trademarks. Hopefully this case will raise the profile of the still relatively unknown multimedia trademark, and more companies will give the animations in their marketing communication the brand protection that these ‘new’ marks deserve.

Bas Kist